Highlights

- The Bank of Canada waited a bit too long to start cutting in 2024, scarred by the memory of sticky inflation in 2023.

- The US economy has now moderated to where Canada’s economy was in late-2023, with a job market showing early but convincing signs of deterioration.

- There’s no need to panic, the US economy is still holding up; the Fed needs to get going, but a 0.25% cut in September is a sufficient start.

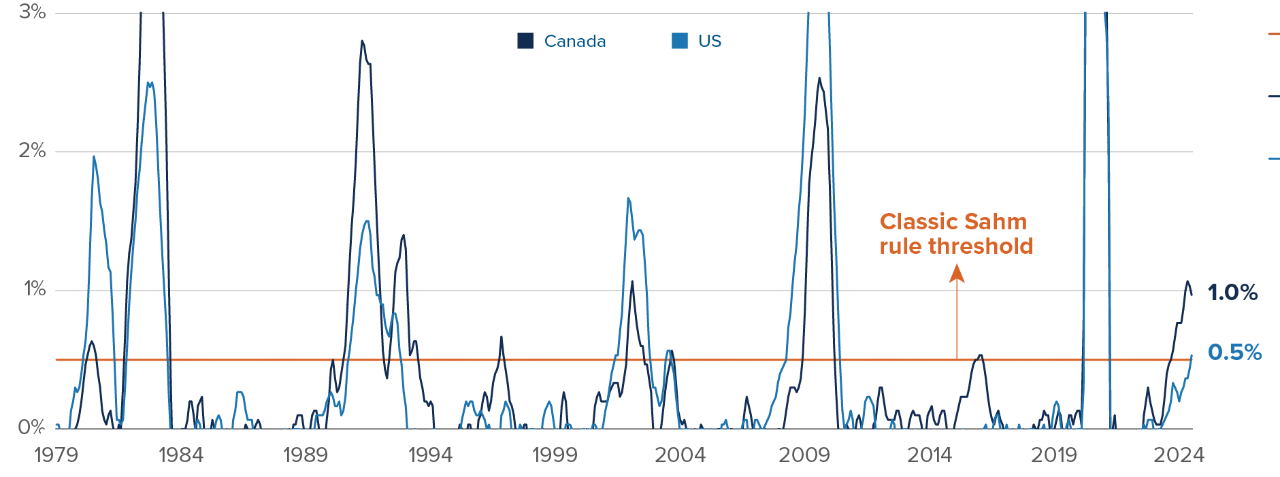

Among major advanced economies, Canada has arguably had the weakest start to the year, while the US boasts one of the strongest. Canadian economic data started heading south at the end of 2023. But the Bank of Canada (BoC) only pulled the trigger on an inaugural rate cut in June, half a year after the Canadian economy began begging for lower rates. A rising unemployment rate triggered the recession-dating Sahm rule back in October 2023, and three-month core inflation dipped below 2% in February 2024.

The US Sahm rule triggered nine months after the Canadian rule

Three-month average unemployment rate minus its low point in prior twelve months

Source: Bloomberg, Business Council of Canada, Global Financial Data. Real-time (first release) unemployment rates when available.

Source: Bloomberg, Business Council of Canada, Global Financial Data. Real-time (first release) unemployment rates when available.

Core CPI inflation has finally dipped below 2% in the US

Three-month core CPI inflation rates

Source: Statistics Canada, US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Source: Statistics Canada, US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The BoC’s patience in approaching rate cuts in the first half of 2024 was slightly misguided, if not understandable after years of sticky inflation. Back in early 2023, Bank of Canada governor Tiff Macklem was a bit too vocal about rates having reached their peak at 4.5%. When the Bank of Canada had to surprise Canadians with two additional rate hikes as inflation spiked, its credibility suffered. This misstep probably somewhat biased BoC officials against rate cuts.

Economic data turned sharply weaker in early 2024, in part weighed down by the rate hikes of summer 2023. We — and many others — advocated for rate cuts at the start of 2024 to jump-start the ailing economy. The Bank of Canada probably waited a bit too long to do so, trying to avoid repeating its 2023 mistake. An initial cut in January, March or April would probably have curbed the further rise in unemployment we’ve since seen.

The US Federal Reserve is now facing the same decision the BoC agonized over eight months ago. The US economy has moderated to where Canada’s economy was in late-2023, with the job market showing early, but convincing, signs of deterioration. The Sahm rule has been triggered. History says a recession is in the cards.

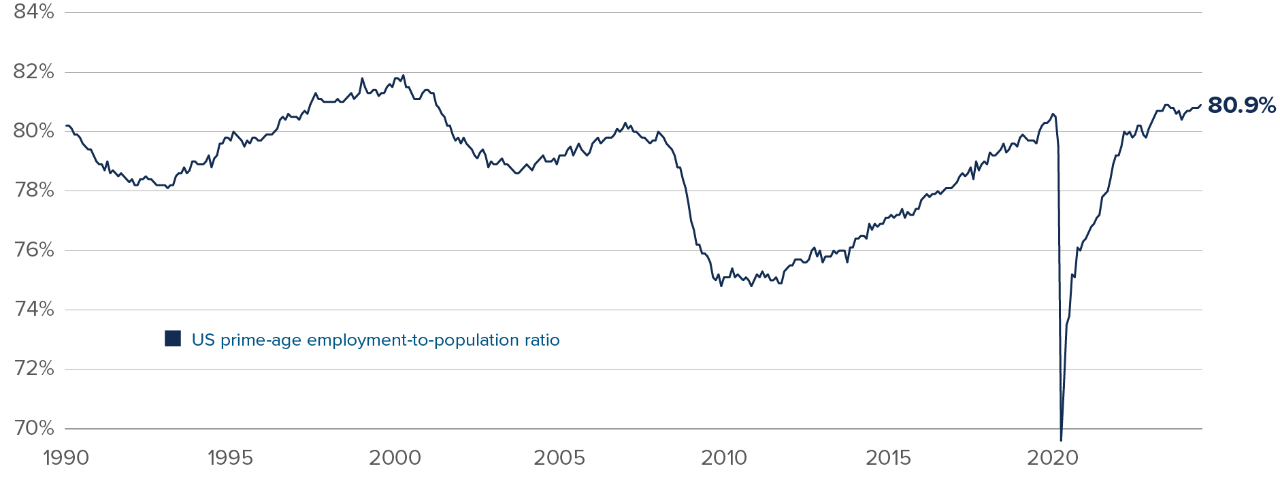

Now, we should take the Sahm rule — derived from the unemployment rate — with a grain of salt. Generally, the unemployment rate is the best leading indicator for the business cycle; rising unemployment precedes outright layoffs. But it’s not the only employment measure to consider. The Household survey, from which the unemployment rate is derived, is significantly gloomier about the job market than the Establishment survey, which counts job creation. The employment-population ratio for prime-age (25–54-year-old) Americans is at a 25-year high. Part of this discrepancy possibly stems from the Establishment survey undercounting population growth from immigration, and so overestimating the employment-to-population ratio. The Bureau of Labor Statistics also recently announced the results of a preliminary revision to job creation which, if confirmed, could bring the year-to-date pace of job creation down to a measly 97,000 per month.

Strong employment data contrasts with the Sahm rule

Prime-age (25-54 years old) employment-to-population ratio

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The benchmark revision clouds the employment picture

US private sector job additions, including the preliminary benchmark revision

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics. The benchmark revision of -819,000 covers the April 2024-March 2024 period. Here, we assume that the preliminary revision carries more recent months.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics. The benchmark revision of -819,000 covers the April 2024-March 2024 period. Here, we assume that the preliminary revision carries more recent months.

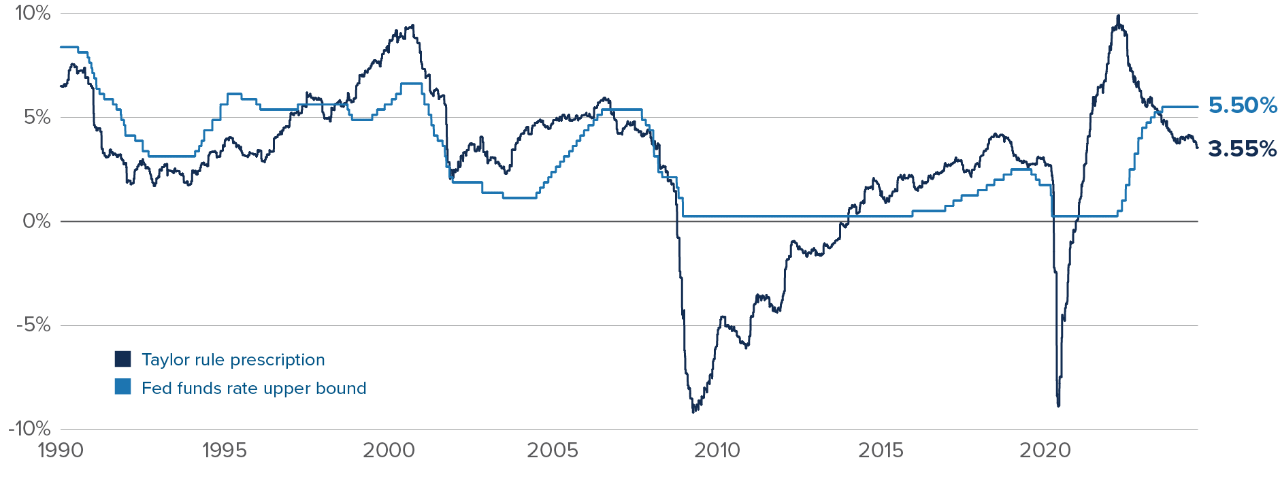

In our view, the US economy is clearly weakening, but is not in the early stages of a recession. Federal government spending is still in overdrive, boosting growth. A succession of Fed rate cuts would suffice to stabilize the downtrend in the labour market. But the Fed needs to get going quickly.

The Fed needs to cut rates to at least 3.5% over the coming months

Real-time Taylor rule prescription

Source: Multi-Asset Strategies Team.

Source: Multi-Asset Strategies Team.

Rising unemployment is a vicious cycle, with job losses snowballing into weak consumer spending and deteriorating business confidence. Our real-time Taylor rule, which bakes in the average economic forecasters’ 12-month ahead views on growth and inflation, is prescribing a policy lending rate around 3.5%. To get there in mid-2025, the Fed needs to embark on a one-cut-per-meeting easing cycle, starting in September. There’s no need to panic. Economic data is ambiguous, and “animal spirits” are still cheery. But the Fed shouldn’t wait for unambiguous signs of a downturn to begin cutting, as the BoC unfortunately did.

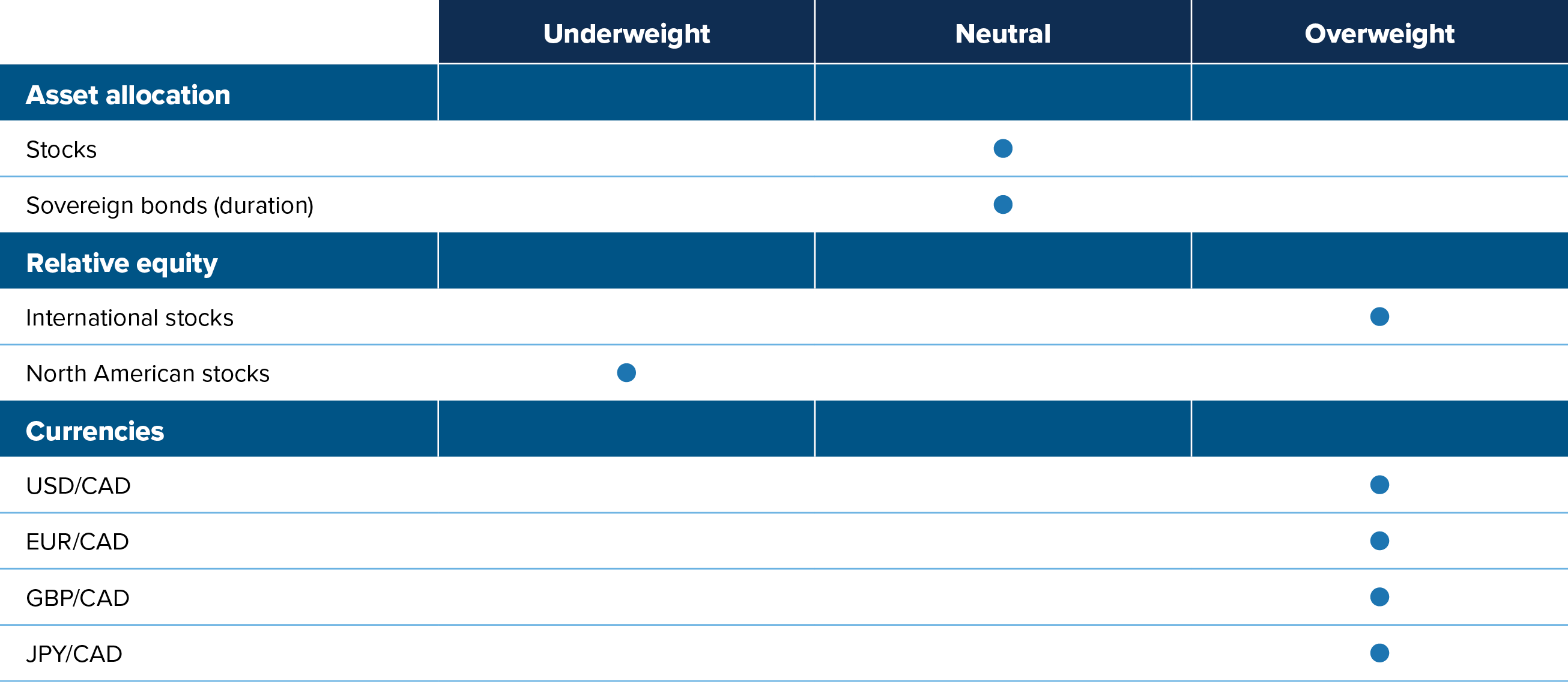

Multi-Asset Strategies Team’s investment views

Tactical summary

Note: The views expressed in this piece apply to products that are actively managed by the Multi-Asset Strategies Team.

Positioning highlights

Turning neutral on duration: We’ve mostly shied away from duration over the past few years. We preferred leaning into stocks for returns and saw US recession odds as overblown. We tweaked this view in early July, turning neutral on duration. In the Global Macro Fund, we notably added bond exposure through short-term two-year government bonds, betting on anticipated rate cuts by developed central banks.

Still not ready to bet against equities: While global stock markets are clearly expensive, valuations are not at extremes, as they were, for example, at the end of 2021. Investor positioning is supportive in the medium term, and we expect the US to avoid a recession as a slew of rate cuts help stabilize the economy. This leaves us with a broadly neutral view on global equities.

Overvalued North American stocks: We generally don’t like North American stocks, whether Canada or US, relative to other opportunities worldwide. Not only do international stocks generally have more attractive valuations than North American assets, but they should also benefit from promising macro catalysts ahead. China’s economy is stabilizing, if not bouncing. European and, to a lesser extent, Japanese stocks, benefit from a macro stabilization of China.

Taking profits on real estate: Real estate had been our favourite equity sector since the end of May, partly as a bet that interest rate cuts would provide relief to the embattled property sector. With markets now pricing in eight rate cuts over the coming year, we’re trimming our position.

Canadian landing: The macro situation in Canada is much more dire than in the US. The Canadian economy has an argument for the most disappointing advanced economy year-to-date. The job market is deteriorating quickly, especially when adjusting for working population growth and government hiring. We have been adding to our short Canadian dollar position, already one of the largest bets in the Mackenzie Global Macro fund.

Commodity-exporting EM currencies: Commodity-exporting EMs are well situated to outperform in this macro environment. Their budgetary and external balances have improved amid high global nominal growth and high commodity prices. Their central banks started raising rates much earlier than the rest of the world. As a result, they have generally reached the end of their tightening cycle, reducing the risk of overtightening into a recession. But the level of rates remains high, offering positive carry over most other currencies. On the other hand, we hold a negative view on the currencies of Asian EM countries. Their external positions have severely deteriorated, and their interest rates are relatively low. Thailand’s prospects have improved significantly, but Korea and the Philippines are still stuck in the macro mud.